January temperatures third highest on record-Report

The extended spell of high global temperatures is continuing, with the Arctic witnessing exceptional warmth and – as a result – record low Arctic sea ice volumes for this time of year. Antarctic sea ice extent is also the lowest on record.

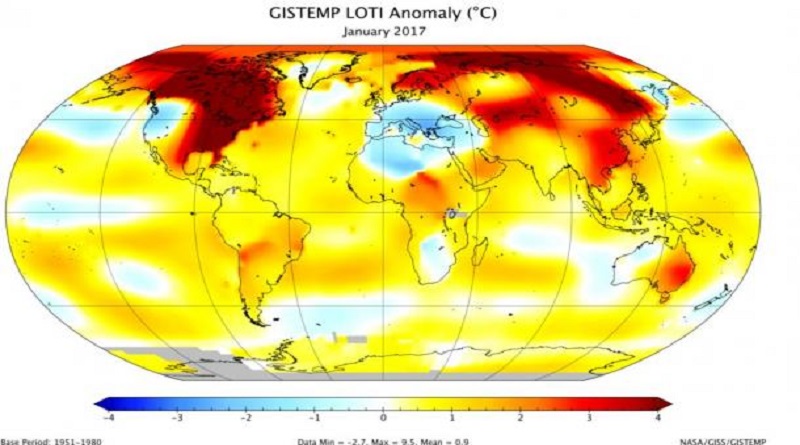

Reports from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies said that global average surface temperatures for the month of January were the third highest on record, after January 2016 and January 2007. NOAA said that the average temperature was 0.88°C above the 20th century average of 12°C. The European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts, Copernicus Climate Change Service, said it was the second warmest.

Natural climate variability – such as El Niño and La Niña – mean that the globe will not break new temperature records every month or every year. More significant than the individual monthly rankings is the long-term trend of rising temperatures and climate change indicators such as CO2 concentrations (406.13 parts per million at the benchmark Mauna Loa Observatory in January compared to 402.52 ppm in January 2016, according to NOAA’s Earth Systems Research Laboratory).

The largest positive temperature departures from average in January were seen across the eastern half of the contiguous U.S.A, Canada, and in particular the Arctic. The high Arctic temperatures also persisted in the early part of February.

At least three times so far this winter, the Arctic has witnessed the Polar equivalent of a heat wave, with powerful Atlantic storms driving an influx of warm, moist air and increasing temperatures to near freezing point. The temperature in the Arctic Archipelago of Svalbard, north of Norway, topped 4.1°C on 7 February. The world’s northernmost land station, Kap Jessup on the tip of Greenland, swung from -22°C to +2°C in 12 hours between 9 and 10 February, according to the Danish Meterological Institute.

“Temperatures in the Arctic are quite remarkable and very alarming,” said World Climate Research Programme Director David Carlson. “The rate of change in the Arctic and resulting shifts in wider atmospheric circulation patterns, which affect weather in other parts of the world, are pushing climate science to its limits.”

As a result of waves in the jet stream – the fast moving band of air which helps regulate temperatures – much of Europe, the Arabian peninsular and North Africa were unusually cold, as were parts of Siberia and the western USA.

Sea ice extent was the lowest on the 38-year-old satellite record for the month of January, both at the Arctic and Antarctic, according to both the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center and Germany’s Sea ice Portal operated by the Alfred-Wegener-Institut.

Arctic sea ice extent averaged 13.38 million square kilometres in January, according to NSIDC. This is 260,000 square kilometersbelow January 2016, the previous lowest January extent – an area bigger than the size of the United Kingdom. It was 1.26 million square kilometers (the size of South Africa) below the January 1981 to 2010 long-term average.

“The recovery period for Arctic sea ice is normally in the winter, when it gains both in volume and extent. The recovery this winter has been fragile, at best, and there were some days in January when temperatures were actually above melting point,” said Mr Carlson. “This will have serious implications for Arctic sea ice extent in summer as well as for the global climate system. What happens at the Poles does not stay at the Poles.”

Antarctic sea ice extent was also the lowest on record. A change in wind patterns, which normally spread out the ice, contracted it instead.